Editor’s Note: I am missing this so much right now. I have made eight trips to Patagonia over the past decade, and have been there for the past six Januarys. There is a feeling of sadness and passing that make me wonder about my future with this place and the choices I have made to remain in North America this winter.

I hope you enjoy this memory from my last sojourn up Fitz Roy, with Jake Perkinson

January 2016 — I look upward. To the left is the “5.7+” chimney “I can’t fall out of”. To the right is Chouinard and company’s original path. Rumor has it, the 6a+ off-width is supposed to be a struggle. “Go left” was the third hand Colin Haley beta. If anyone knows the range, it is him.

Much like the pitches below, bits of ice and snow grace the cracks and faces. The rope snakes away from my waist, off around a corner, through an extended piece and down to Jake, thirty feet below me, out of sight, but not out of mind. I continue upward, consciously forgoing gear in the name of less rope drag. With the Colin beta in mind, I move up left and clip a piton. I spy a slingable chockstone but nothing else that looks like it will afford any protection. I stem, smear and jam, hyper-aware of the patches of verglas occasionally coating my path. Slinging the chockstone comes smoothly, a carabiner on a sling tossed over the rock. I secure it with a girth hitch and clip in my rope. Next, I think, I need to get my feet on to the chockstone. I grab the stone, and with my left side into the crack attempt an arm-bar. Despite the “5.7+” nature of the crack, it is a struggle for me to move up and past the stone. A foot, another arm-bar and I am off. “Falling, falling…” I yell as I tumble over backwards, headed the wrong way on a one way street.

****

The Californians had done it over three nights. The Brits had bailed off of it and Colin Haley had soloed it. We figured maybe, we could fit somewhere into that spectrum.

We were fresh from a recent bail off of the Fitz Roy’s Pilar Goretta due to not being strong enough (this seems to be a theme, with me as the common denominator). Jake was looking at dwindling days before he had to return to work. We were both looking at a not so inspiring window of OK weather.

The weather window looked small and given our previous performances on varying routes of differing difficulties, it wasn’t a gimmie. Getting up, and down, Fitz Roy in the “window” would require a small dose of toughening up.

The plan was simple, if not somewhat flawed. As per usual we had overestimated our ability or underestimated Fitz Roy’s size.

The Brits had bailed. They had gotten a bit lost, not traversing far enough across the ledge system before launching upward. Several pitches up they realized they were off route, it was a bit too icy and they were moving two slow. So turn around and head home it was for them.

Colin Haley hadn’t found the conditions to be too icy though and had soloed the route not long after the Brits had bailed. His was the fifth recorded solo of the route. Of course we weren’t Colin Haley. He had passed beta to the “old guys” which is what we had taken to calling the Californians (who weren’t even all from California) and who, despite, or maybe because of the moniker, had our respect and admiration. “The crux pitch has two options”, Haley had said. “Right is the original route but left is an easier 5.7+ chimney that you can’t fall out of.”

“You guys will cruise it” Steve, one of the Californians, had said in his usual, confident fashion. A week prior or so he and his comrades had spent several days up on Fitz Roy, toughing it out in a fashion that Jake and I could never quite emulate, least ways I couldn’t. Rumor has it they spent three nights on Fitz Roy’s cold, south side without bivy gear. They were cut from a different cloth, had cut their teeth in a different era.

****

We left town at 1 pm. The twelve kilometers to Laguna de los Tres were mostly uphill. We moved quickly on the well beaten path despite the endless questions from the trekkers: “you climbing Fitz Roy?” “All the way to the top?” and “how long will it take you?” We would politely answer then move on.

“We might just be taking our gear for a walk” Jake said somewhere not far from town.

“Yep, maybe so, but I guess we don’t know if we don’t try” I said. “Lets get up there and find out.”

Later as we lay out our sleeping bags for our bivy at the lake, Jake asked me a question. “You have the breakfasts right?”

“You mean the two bags of oats?” I replied, a bit skeptical before thinking and pausing. Then: “No, you were carrying the food, I had the rack.”

“Well, we have potato chips and cookies… That should do something.” After a quiet moment, in usual, positive, Jake fashion, he made lemonade. “Hmm, I guess we are going fast and light.”

“I still have a sandwich left from today” I added, feeling a bit guilty about not thinking to pull the bags from the stuff sack back in town.

“Light and fast.” Not much more is said about it for the next 48 hours.

Our late start, no time consuming breakfast notwithstanding, the next morning found us slogging through soft snow first on the Glaciar de los Tres to Paso Superior then across Glaciar Piedras Blancas up to La Brecha de los Italianos. We paused briefly at Paso Superior to refuel and rope up, quite aware of our glacial pace and softening snow. None-the-less we moved onward. I led up the glacier, first mellow then steepening and softening as we gently and cautiously stepped across the bergschrund. It was two steps forward, one step back as we slowly wallowed upward, dripping in sweat, soaking in snow, and frying from sun. As the upward angle lessend, I traversed right aiming for the growing cold of the shade and more palatable rocky ground. A few mixed moves of rock and ice found me at a suitable belay station. Jake though was seventy meters behind, still traversing steep snow in the blinding sunlight. I belayed him in and we swapped leads. His lead took us up 30 meters to a ledge; from there I led to the top. La Brecha, at last. After a quick downclimb we paused and enjoyed the western aspect and it’s warm sun. We filled our bottles and made dinner before doing a final pitch to La Silla, where we set up our bivy. It was 9 pm.

Seven hours later Jake lead out across the ice at the top of Couloir Poincenot. I crept along the 45° hard snow and ice, keeping our pace to a crawl. The lower angle slopes at the base of the south face gave reprieve and we quickly gained the bergschrund and ice below La SIlla Americana. After fixing an ice axe belay into the snow, and belaying me in, he launched upward onto the steeper ice. Two pitches and twenty meters of simul-climbing later we gathered up at the base of the Californiana and swapped leads.

The long traverse at the top of pitch two is where the Brits had gotten lost, going up before traversing far enough left. Despite the heinous rope drag, I went too far. The long ledge was littered with loose blocks and rope pinching crevices, so running the rope through some directionals provided safety while simultaneously making forward progress slightly more difficult. So when Jake arrived and we swapped gear, I scouted left for a better view. Above me a big corner system revealed two chimney/off-width options. “Well that seems to be it” I said to Jake. Looking at the picture in my hand I could see that I actually wanted to enter the corner system from back right and further above. “I am going to go back right and then up” I said as I walked back towards him. He pulled in the slack and I scrambled up right, then back left across a small ledge system. “Rope drag, watch the rope drag again” I think to myself. Thirty feet up, a piece of protection with a long sling protected a move left.

Much like the pitches below, bits of ice and snow grace the cracks and faces. The rope ran down to Jake, forty feet below me, out of sight, but not out of mind. I continue upward, consciously forgoing gear in the name of less rope drag. I move up left and clip a piton. There is a slingable chockstone but nothing else that looks like it will afford any protection. I stem, smear and jam, hyper-aware of the patches of verglas occasionally coating my path. Slinging the chockstone comes smoothly and I clip my rope to it. Next, I think, I need to get my feet on to the chockstone. I grab the stone, and with my left side into the crack attempt an arm-bar. Despite the “5.7+” nature of the crack, it is a struggle for me to move up and past the stone. A foot, another arm-bar and I am off. “Falling, falling…” I yell as I tumble over backwards, headed the wrong way on a one way street.

The backpack hits the rock first, its relative softness padding the blow. I slide downward, hoping to stop. Something catches me. “Halfway” I hear floating up from below. A moment passes and the adrenaline kicks in. I right myself, stand up and my mind starts racing. The thoughts come in quick succession: am I hurt? what now? do I try again? do I bail? Above me the rope runs up, about ten feet, to the chockstone. It is relatively tight. “I’m alright” I yell down to Jake. There is no response. “OK, well I guess I just keep going up” I think to myself. “Can’t fall out of?” I think next. “Proved that one wrong.”

The immediate security of gear invites me back right, to the original line. I add a long sling to the chockstone, clip my pack to dangle below my harness and start grunting up the four inch crack. Despite a lack of gear and long slings, somewhere along the line the rope drag becomes heinous and gravity becomes stronger. “Fuck that is like a number five sized crack” I curse to no one in particular. There are a couple of fixed pieces at my feet, but the number four in my hand clanks uselessly inside the knee width, slanting crack. Ten feet up, it constricts and there is a ledge. I pull on the rope below me and feel it’s resistance. I look at the crack above and feel my resistance. I slide in, knees and handstacks. I wiggle. I thrash. I grunt and swear. I don’t want another whipper. Not here, not now. It would hurt. I back down. “Watch me Jake” I yell down.

“You got it, I’m with you” he replies. “Nice work up there.”

I curse my rope drag and think of the lay back. I scan for ice. I scan for gear. I find neither. I try the straight in technique again. I make it no higher. I back down. “Fuck it. If not me who, if not now when.” The rope pulls hard on my harness as my feet push onto the rough white granite. Bloodied hands, like stumps on another body, pull painlessly on the rounded crack. I inch upward. I’m pulled downward. “Goddamn vision quest” I mutter. Somehow, I do not fall. Somehow, despite the rope trying it’s damnedest, my feet don’t pop off, my hands don’t give way, my will doesn’t give out. A crack appears in the back and breathing heavily and deliberately through pursed lips, I shove in a #1 Camalot, yard up the rope and clip it. Five minutes later, it is “off belay, Jake” as I situate myself and arrange the belay.

“Thank you Jared” he yells up. “It seemed pretty hard and awkward, should I jug?”

“Sounds like a good idea” I respond. Then: “line is fixed.”

I pull some water from the pack and nibble on a ProBar. Several hundred meters below the Torre Valley is awash in sunshine. Slowly my heartbeat returns to normal. Twenty minutes later, Jake’s grunting and scraping tell me he has entered the chimney. Soon enough he joins me at the ledge. “Nice work on that. It seemed like you had horrible rope drag huh?” He says nothing about my fall.

“Yeah, I tried extending the slings and not placing gear, but it musta been that corner down low. You know I took a whipper down there, right?” I say quizzically.

“Really, I didn’t catch any sort of fall.”

Yeah, about ten feet. Upside down. Fell out of the 5.7 chimney that you can’t fall out of” I say. “I fell on the chockstone. That’s why I went right. I tried left, but fell out. Icy…” I tail off.

“Well, you got another one in you?” he says.

“Yep, I figure two more, that will give us each five.” I grab the gear and start re-racking.

****

We kept looking up, kept eating and drinking, climbing and belaying. A splitter handcrack and a few ice filled pitches lead us up to and across the windswept summit ridge. As clouds swirl around nearby spires, we trade climbing shoes for boots and coil our ropes. We plod upward and sunset finds us standing on the summit of the tallest peak around.

The light begs us to linger and I toss out the idea of summit bivy. We can it though, in favor of the warmth of movement and the solace of “doing something” and rappel into the growing dusk. Twelve hours and one snow night-long snow squall later we stroll into our high camp, a whole lot more tired and another mountain adventure richer. After catching twenty minutes of shut eye, we pack up, rappel La Brecha, posthole to Laguna de los Tres and pound the twelve K of trail back to town, at last draining both our headlamp batteries and our reserves. Cervezas and milenesas await.

Guidebook author Rolando Garobotti says “that a competent party should be able to do this in a day from Paso Superior or even from Laguna de los Tres.” He also writes “the rock is quite good, but there is nothing special about the climbing” Colin Haley said it was impossible to fall out of the chimney. Our 30 hour round trip excursion from La Silla challenged a few ideas, the obvious ones being that we thought we were a competent party and that one can’t fall out of the 5.7 chimney. Was the climbing special? Hard saying. I found the cracks and position to be enjoyable. Always good belay ledges, easy route finding, and not much loose stone. For me, it was a memorable day in the mountains. I guess that makes it special. Does it disprove anything? Nope, it is just a different opinion.

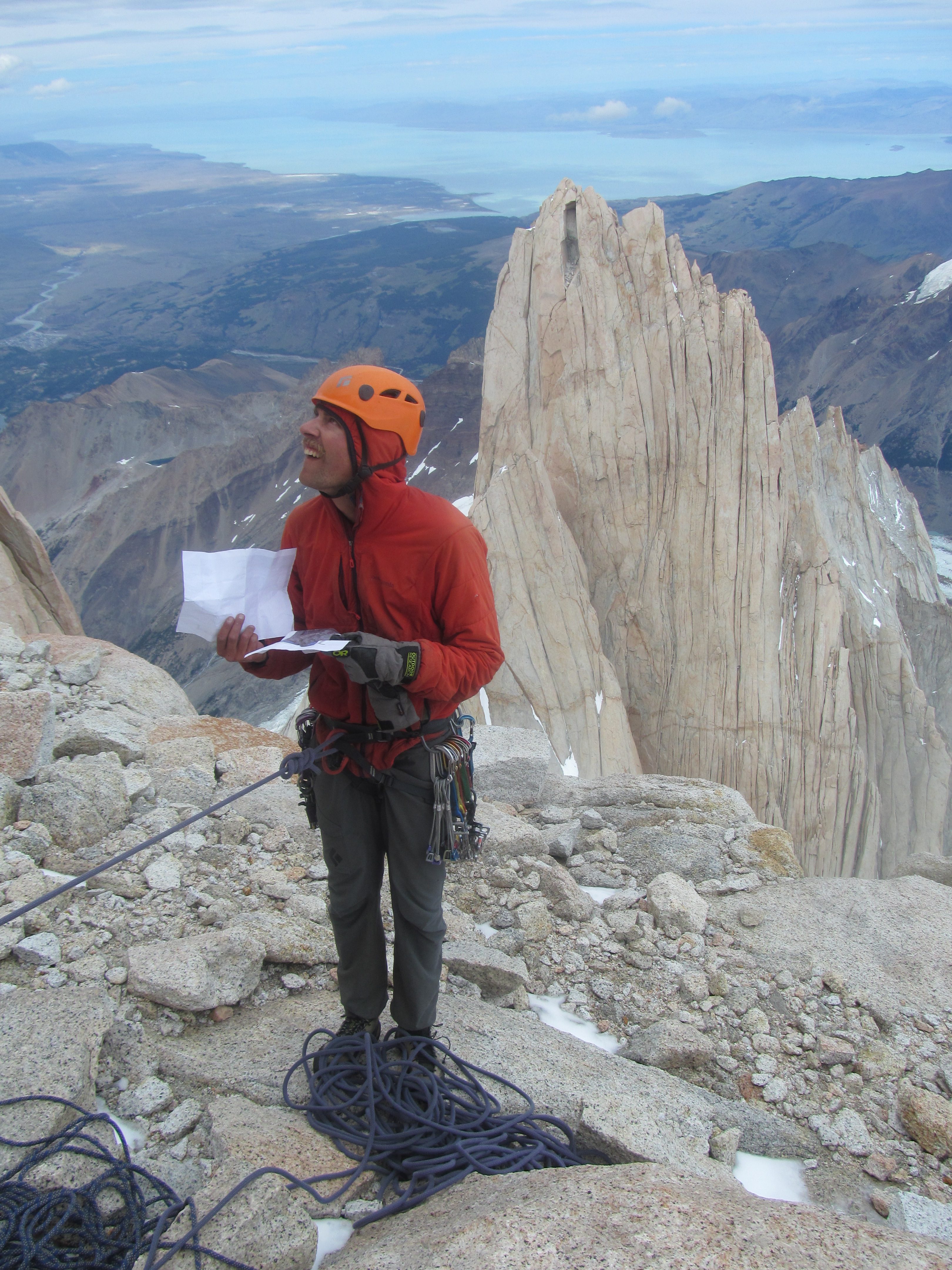

Featured Image: The Torre Group from high on Fitz Roy’s west side.

Be First to Comment